A Hucknall History

HUCKNALL -- the PLACE-NAME.

Hucknall Torkard - Hucknall-under-Huthwaite - Ault Hucknall

A visiting American scholar, enjoying a sabbatical researching Domesday England, dropped in on the Ashfield Historian in 1995 and agreed to take a look at our ancient district in the light of his researches. Here is Dr Grant's promised paper.

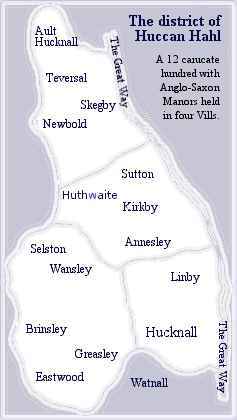

Professor Ekwall suggested that the name of Hucknall was, in its original form of huccan hahl, initially a district name. With three Hucknall names close together (Ault Hucknall, Hucknall-Huthwaite, and Hucknall Torkard) it makes sense to assume that these represent three settlements where the district name subsequently crystallised into village names, each later having distinguishing epithets attached. This view of the significance of the name is now generally accepted by nation and local scholars. Indeed, it would not be surprising if it were not, for the meaning of the name is "Hucca's corner of land", and it is hard to imagine that three separate places within such proximity should each be described as a corner of land belonging to (or under the authority of) the same man.

The hahl - the termination of the name - was frequently used for a corner of something larger, and it does not make sense to assume three separate 'corners' of such a small overall area, each bearing originally the same name. The prefix 'Ault' is Norman French (meaning 'high', or 'heights of') and the suffix 'Torkard' is a manorial name indicating the later ownership of the Torchard family. These epithets thus came considerably later than the Hucknall names.

If these scholars are correct in the 'district name' interpretation of Hucknall, then the implications for local Anglo-Saxon history are profound, and only one scholar appears to have drawn the logical conclusion, that the three Hucknalls were once not only parts of a single district, but that this district was a political and administrative entity, in the sense of being under the control of one leader, the eponymous Hucca.

The creation of the counties of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire came much later than the Anglo-Saxon settlements of the region, and those scholars who argue against the 'district' theory on the grounds that one of the Hucknall is now in Derbyshire are making the obviously nonsensical assumption that a later county boundary had the earlier effect of bisecting a district.

We can be entirely scientific about this. We can take the assumption of the correctness of the 'district' interpretation, make deductions from that assumption, and see if those deductions are in accordance with known facts.

THE HYPOTHESES. Before proceeding, we need to precisely define the exact hypotheses which we are making. These are:-

1) That huccan hahl was a district which included the settlements, later named Ault Hucknall, Hucknall-under-Huthwaite and Hucknall Torkard, as well as others.

2) That the district of huccan hahl was a single political entity, originally under the control of an Anglo-Saxon chieftain or sub-chieftain called Hucca.

3) That in the course of time the district became formalised into a 12-carucate hundred which, with modifications after the Norman Conquest, can be traced in the Doomsday record.

If indeed huccan hahl (district) was a political entity, what was its extent and what kind of district was it?

We can get an idea of the extent just from looking at the map. From Ault Hucknall in the north to Hucknall Torkard in the south there are about ten miles of high land -- the highest point in Nottinghamshire. The area we are seeking to define might be larger that this stretch between the two Hucknalls, but it cannot be smaller, and in the case of the southern boundary we must exclude Watnall because that was someone else's corner of land. The east west extent is more difficult to arrive at, but a combination of geographical and socio-political facts gives us the strongest clues. To the west of the area is a great scarp, dipping steeply westwards into Derbyshire and sloping gently esstwards into Nottinghamshire. If a boundary had to be anywhere it would have been there. The eastern boundary is little more difficult, but research on the medieval 'Great Way' through the area suggests that this route marked the eastern boundary of huccan hahl.

The road known as the Great Way has been written about extensively in its Yorkshire sections, but few have studied its section through Ashfield. They showed that the road pre-dated the formation of the Anglo-Saxon estates because it forms a complete linear boundary between those estates. This suggests that it would do so in its Nottinghamshire sections, and therefore it can be looked at to see if it forms the eastern boundary of the huccan hahl hundred. In fact we have information about it from the 1232 Perambulation of Sherwood Forest, which treats the road as a boundary. This clearly indicates that the road enters the district at Newboundmill Bridge, becomes Dawgates to Skegby, Forest Road to Eastfield Side, where it separates Sutton from the forest, thence via Blackmires to the site of the Newstead hospital, and from there south to Papplewick. The section through what is now Newstead Abbey grounds was closed in 1764 when, on the promotion of Lord Byron, a new road was made from Larch Farm to Red Hill.

THE 12 CARUCATE HUNDRED.During the medieval period there was a type of government area which is referred to as the 12-carucate hundred.

The carucate, originally a land measure but later fossilised as a taxation unit, consisted of a 8 bovates. This type of hundred (not to be confused with the standard hundred of Doomsday) was generally subdivided into four sub-units or vills, each of three carucates or 24 bovates.

Between the sections of Domesday dealing with Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire there occurs the following:-

1. In Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, if the King's peace, given by hand or seal, be broken, a fine is paid through the 12 hundreds, each hundred £8. The King has two parts of this fine, the Earl the third, ie 12 hundreds pay the fine to the King six to the Earl.

The text appears here to be referring to a 12 carucate hundred, as we can see from the amount of the fine. £8 was 12 marks or 120 Danish ora, and 120 is the number referred to as a long hundred. The text also indicates that these hundreds are of some antiquity already, in its reference to 'the Earl'.

That there were only 18 such hundreds in the two counties indicates that the nature of this type of hundred was rather unusual, for this would amount to only 216 carucates in the two counties, which is a mere fraction of the total carucatage. The system of collective fines suggests that there was something particularly sensitive about these areas, necessitating a form of punishment which is demonstrably unfair, with the innocent paying for the sins of the guilty, this could only be justified if the King's peace was particularly important in the areas so designated. This sets the fine at 120 ora per {long} hundred, which is ten ora {one mark} per carucate. This equates to 1/8d per bovate.

Unfortunately Domesday does not indicate directly where each of these 18 hundreds are situated. Only three are mentioned by name in the Nottinghamshire, Domesday (Blidworth, Southwell and Plumtree) but there are indications of others. Most Danish areas of England have their Domesday carucatages calculated in three, six or twelve carucate units, which of course fit well into the 12 carucate assessment of the hundred we are describing.

Peters was the first to show that an area roughly conforming to what we have defined as huccan hahl conveniently fits into a 12-carucate grouping. Following further research by Capt Peters and the author, this analysis has now been given further refinement.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SUTTON & SKEGBY.In Domesday, both Sutton and Skegby are listed as part of the King's Manor of Mansfield, and this has led some local scholars, from Lindley through Bonser to Clay-Dove, to deny that Sutton was ever itself a manor.

This view is untenable: apart from the obvious fact that what pertained at Domesday is no proof of what pertained later (or indeed earlier) those authors are inconsistent in that they do not deny the later manorial status of Skegby. In fact, in 1207, Skegby was separated from the Soke of Mansfield.

Sutton also changed hands, and saw its major development as a manor within the Cavendish Estates.

If Sutton and Skegby became independent manors some time after Domesday, which is certainly the case, we cannot aver that they were not also independent at some time before Domesday.

The suggestion that they were indeed only a temporary adjunct to Mansfield is supported by the carucatage of the King's manor, which amounts to thirty bovates, or three carucates and six bovates. Since the standard Nottinghamshire assessment was in units of three carucates, the extra six bovates of the Mansfield Manor looks very much like a non-permanent and previously unplanned annexation. (It is perhaps significant that Skegby and Sutton are the only parts of the Mansfield listing which are not duplicated. All the other attachments to the royal manor are listed separately in following entries.) If this is the case then we can assume that those six extra bovates were the valuation for Sutton and Skegby together. It is in fact the assignment of these six bovates to the two Ashfield villages which enabled Peters to show a huccan hahl fit with a twelve-carucate hundred.

THE PLACE OF AULT HUCKNALL.Where Peters' figures needed to be somewhat modified was in the fact that he was at first reluctant to assign one of the two Domesday Hucknall references to Ault Hucknall (or to Hucknall-Huthwaite) perhaps too diffidently following all previous Domesday commentators in assuming that the two references were to Hucknall Torkard.

Peters later accepted that one of the two Hucknall references must be in northern Ashfield.

That both these references are in the Nottinghamshire Domesday and Ault Hucknall is now in Derbyshire can be dismissed as irrelevant to a situation which was defined before the establishment of the two counties.

The two Hucknall references in the Nottinghamshire Domesday area as follows:-

LAND OF WILLIAM PEVEREL. In Hucknall two brothers had 4 bovates of land taxable. Land for ½ plough. 3 villagers have one plough. Value at the time of Kind Edward, 8s. now 4.

LAND OF RALPH OF BURON. In Hucknall Ulchet had 12 bovates of land taxable. Land for two ploughs. Osmund, Ralph's man, has one plough and 5 villagers who have 3½ ploughs. Woodland pasture 1 league long and ½ wide.

In deciding which of these two references should be assigned to the north of th district there is one argument which eliminates the Buron land, for it's assessment is too high. The 4-vill split of the 12 carucate hundred assigns three carucates to each vill. The northernmost vill must include Newbold (Newbound) of 12 bovates and Teversal of 6 bovates. This leaves only 6 bovates to make up the vill, so the Buron Hucknall must be excluded, leaving the Peverel Hucknall as the sole candidate.  The four bovates of this manor bring the total to the northernmost vill to 22 bovates, two short of the 24 bovates needed. If the 6 bovates from Sutton and Skegby are split with 2 to Skegby and 4 to Sutton (a reasonable ratio) then we have an exact 24 bovates or three carucates for this northern vill of huccan hahl.

The four bovates of this manor bring the total to the northernmost vill to 22 bovates, two short of the 24 bovates needed. If the 6 bovates from Sutton and Skegby are split with 2 to Skegby and 4 to Sutton (a reasonable ratio) then we have an exact 24 bovates or three carucates for this northern vill of huccan hahl.

There are other arguments which support this. Ralph de Buron was the progenitor of the Byron family, whose link with Hucknall Torkard is well-known. Its area of woodland (about 720 acres) suggests proximity to Sherwood Forest.

There is another argument which depends upon the reason for Hucca being charged with responsibility for this area.

Its position on the highest land in Nottinghamshire, and its earlier military significance during the Celtic period (exampled by the Huthwaite Iron Age Hill Fort) suggests that the reason for its establishment was a military one. Other Anglo-Saxon place-names from around Huthwaite (Stubbing Hill, the Brand, Rowley) constitute clear evidence of a massive woodland clearing programme during the Anglo-Saxon period itself, as of course does the very name of Huthwaite itself - clearing on the hill spur. Since Britain was pacified during Roman rule there was no need for such native defences, but with the breakdown of Roman rule and the subsequent Anglo-Saxon invasions those very places which had proved of military significance to the Celts would become so again, this time to the early English.

It is possible to show this military significance in the earlier Iron Age, and the historical continuity of the political significance is strongly hinted at in the list of tenants-in-chief of Domesday.

THE DISTRICT OF THE IRON AGE.In addition to the archaeological record, we have a fair picture of the political structure of Britain during the later Iron Age because it had become of interest to the Romans.

The picture we have is of a number of Celtic kingdoms, well documented by the interested Romans, with much further information coming from the Roman Conquest and Occupation.

In the area under discussion, three kingdoms are of interest. Stretching northwards was the kingdom of the Brigantes, probably a federation of smaller sub-kingdoms to the southeast was the kingdom of the Coritani, which during the Roman period had its capital at Leicester; to the southwest was the kingdom of the Cornavii. To which of these three kingdoms did our area belong? It is of course unlikely that we will ever be able to draw precise whole boundaries for these kingdoms, but that should not stop us from seeking whatever evidence there is in particular sections (one of a number of fields of study where local historians can make a significant contribution to national history).

The evidence of coin finds reveals that Coritanian influence extended to Northwest Nottinghamshire and probably into Yorkshire. To this evidence we can add topographical evidence of the great scarp which stretches down from Clowne, above Bolsover, and swinging westwards to Ault Hucknall / Hardwick and then south along the western edge of Ashfield. This is the most obvious place for a western-facing boundary, for such a scarp is militarily more defensive than less elevated regions. The discovery of Iron Age defences such as that on the Huthwaite portion of the scarp, already referred to, confirms the military significance.

It is therefore reasonable to suppose that our area was on the northwestern boundary of the Iron Age Coritani. This naturally gave the area some considerable significance. Although settled on high ground, the Celtic inhabitants would not have had an easy life, for much of the area was marshy, and as agricultural land it fell far below the quality of land in the Trent valley where most of the traces of Coritanian settlement are to be found. Whether or not this high ground supported enough agriculture to make the area self-sustaining cannot now be determined, for we have no information about population levels in the district, but obviously it would compare unfavourably with other parts of the kingdom. Nevertheless, so long as the military need existed then the necessary defending population had to be sustained, almost certainly by some form of provision of food from outside the district. Thus, in the military purpose and in the probable need for the area to be sustained by the rest of the kingdom we have the first inkling of a special status for the district.

THE ROMAN PERIOD.We know that as a matter of general policy the Romans did not suppress the Celtic British kingdoms. On the contrary they generally supported the local monarchies; in the case of both the Brigantes and the Coritani, for example, they built new capitals at Boroughbridge and Leicester respectively. Although their bureaucrats slipped up in the case of the Iceni - resulting in the Boudiccan rebellion - they generally maintained good relations with the local royalty, and encouraged them to receive the benefits of Roman education and civilisation. In the case of the Brigantes, for example they supported Queen Cartimandua against the rebels who were being led by her divorced husband Venutius.

By the beginning of the fifth century when Roman rule had broken down, Britain was left to its own devices both in terms of protection and administration. What more natural than that the breakdown of central government resulted in the Celtic kingdoms asserting their independence not only for tribal reasons but for protection against neighbours.

THE ANGLO-SAXONS.The pirates who had been a thorn in the side of the Romans, raiding the eastern shores of Britain, had considerably more freedom now that the Romans were gone, and the raids which had been a feature of fourth century Britain now became sustainable campaigns of plunder, quite quickly developing into full-scale invasions. These Anglo-Saxons, who would later be called Englishmen, would conquer much of the country in the next one and a half centuries.

It has been said that the Anglo-Saxons re-drew the map of Britain, but this is a misconception, as can be seen by comparing the locations of the Celtic kingdoms with those of the Anglo-Saxon ones which replaced them. True, there are some differences in the south, but those differences can be confidently assigned to the re-organisation under Alfred in his campaigns against the Danes. In fact there is a remarkable correspondence between, for example, the location of the Brigantes and the kingdom of Northumbria, between the Cornavii and the kingdom of Mercia, and between the Coritani and the kingdom of Middle Anglia.

There is every reason why this should be so. We are conditioned by our modern experience of war to assume that during conquest, every inch had to be fought for by the invaders. This was not always so. During a time without a standing army it was necessary for an invader only to overcome the comparatively small war band of the defending king (which might have been augmented to some extent by the conscription of local levies). Once that had been done then the kingdom was open to the invader, and, more importantly, its administration could be taken over and used by the conqueror. There is much evidence that Anglo-Saxon patterns of administration followed the Celtic pattern, which suggests that in most cases the Anglo-Saxons simply adopted and adapted the Celtic systems.

Thus by taking a general view, extending our vision a little beyond the immediate locality and the immediate Anglo-Saxon period, we get a picture of historical continuity from the Iron Age to the Anglo-Saxons. In spite of the all-imposing changes of rule from Celt to Roman, back to Celt and then to Anglo-Saxon, we see a continuity of organisation which each new ruler adopted and adapted for his own purpose.

This throws light on subsequent developments locally. The Anglo-Saxon settlers who have given England most of its place-names took centuries to coalesce into a single united kingdom of England, and much of the history of the English is of military conflict between one kingdom and another. Each kingdom had to defend itself against its neighbours, and that great scarp running down the northwestern border of the territory of the Coritani would need to be re-militarised as it became the northwestern border of the Middle Angles. Having been militarily neglected during Pax Romana it would have to be cleared of centuries of growth and refortified. The evidence is in the 'clearing' place-names, - Huthwaite, Rowley, the Brands, Stubbings.

With such a task, and for such a powerful reason, we have the reason for the region being placed under one Anglo-Saxon leader. The first such leader of the area in question, or at least the first one for whom we have a name, was Hucca.

The area named as Hucca's corner of the kingdom, or huccan hahl, now comes to us as an area where the name survives as the northern and southern entry points.

THE DOMESDAY RECORD.Before considering details of the Domesday record it is important to establish its relevance for the pre-Domesday period. In fact this is implicit in much of the record, for it not only sets out the situation in 1086 but also gives the picture TRE (tempore regis Edwardi, ie in the time of King Edward - poor old Harold being of course ignored).

The mention of the Earl, as previously indicated, obviously refer to an earlier situation since there was no earl in 1086. Comparison between TRE and the 1086 situation how that the changes in ownership did not involve a breakup of the previous manorial system, which continued as before.

Having defined the boundaries (Ault Hucknall to Hucknall Torkard and Ashfield Scarp to Great Way), we can see from the map which parishes area included and check these in Domesday, listing their carucatage. This is done in Table 1.

The table shows a remarkable confirmation of the 12-carucate hundred concept, since our delineation of the boundaries was independent of the above Domesday record, being based on the Hucknall place-names, the military geography of the Ashfield Scarp and the line of the Great Way which is known elsewhere to have formed the boundaries of parishes.

It might be argued that, since most Nottinghamshire assessments were in units of three, six, or twelve carucates, then such a grouping could be made almost anywhere. But that argument ignores the fact that nowhere in the area considered is there a single 3-carucate manor, the largest being 1½ carucates (12 bovates). and some are not even aliquit parts of a carucate (Selston with ⅜ carucate and Wansley with ⅝). The fact is that we have defined an area according to one set of criteria, and found that it was assessed according to another criterion (Domesday) at 12 carucates.

Is it possible to refine this arithmetic further, to see if it conforms to the second feature of a 12-carcate hundred, ie that it can be geographically divided into four vills, and that each of these vills will consist of three carucates?

If above analysis is to be dismissed as mere coincidence then it would stretch co-incidence beyond belief if further analysis also conformed to the 12-carucate hundred layout, purely by chance or manipulation.

The northernmost vill must include the northernmost manors, and these are: Ault Hucknall, Teversal, Newbold and Skegby.

This gives us:- 4 + 6 + 12 + 3 = 24 bovates. (= 3 carucates for the northern vill.)

In fact it works out for the total of all the manors, as can be seen in the following table. (Table 2)

The correspondence is thus far too great for coincidence. The conclusion that huccan hahl consisted of those manors in Table 2 was twelve carucate hundred, is inescapable.

CARUCATES PLOUGHLANDS AND PLOUGHS.The figures in Table 2 giving carucates and bovates (at 8 bovates to the carucate) are actually figures for the geld, ie they are the units upon which tax was calculated. The word 'carucate' derives from the Latin for 'plough', and was originally conceived as the area of land which a plough team of eight oxen could handle. It was considered to be the approximate amount of land which could sustain a family.

Carucatage defined

within huccan hahl

Manors bovates

Newbold * 1 12

Teversal * 1 6

Kirkby * 2 12

Annesley * 1 8

Hucknall * 2 16

Linby * 1 12

Brinsley * 1 4

Greasley * 2 8

Eastwood * 1 4

Selston * 1 3

Wansley * 1 5

Skegby + Sutton 6

Total bovates = 96

The notional family in question must have referred to a manorial family, and hence included the land necessary to sustain the families of the manorial dependent workers.

That the term moved away from this particular meaning is illustrated by the fact that most manors were less than one carucate. Some indeed were only one-eighth of a carucate. Long before Domesday the word had fossilised into a taxation unit.

A more accurate assessment of the amount of land involved in Domesday manors is indicated by the term 'land for x ploughs', since this gives a more obvious link with area.

The actual land which needed to be ploughed did not always exactly equate with the number of ploughs (and teams) available, so Domesday gives a third figure, which is the actual number of plough teams.

A complete analysis of what correspondence there might be between these three different 'plough' units is almost impossible in the general case, for the full figures were not always recorded, or have been lost.

Table 3 shows, for the four vills, the carucates, land for ploughing, and numbers of ploughs. The table has to omit Skegby, Sutton and Eastwood because Domesday does not give a complete record.

Northern Vill #1

Newbold 12

Teversal 6

Skegby 2

Ault Hucknall 4

Central Vill #2

Sutton 4

Kirkby (2) 12

Annesley 8

Southeast Vill #3

Hucknall Torkard 12

Linby 12

Southwest Vill #4

Selston 3

Wansley 5

Brinsley 4

Greasley (2) 8

Eastwood 4

There are thus about five times the number of ploughs as carucates, and more than four times the notional amount of land for ploughing.

Perhaps the most revealing thing in Table 3 is the variation between the number of plough teams. The central vill has about twice the number of teams as two of the other vills, and about three times that of the south-western vill. Kirkby (with sixteen teams) and Annesley (with eight) must therefore have been the 'bread basket' of the hundred of hucann hahl.

Although the figures for ploughland and ploughteams are not given for Sutton and Skegby, a reasonable estimate - based on the figures in Table 3 - suggest that Skegby might have had one plough team and Sutton two teams. In the Mansfield record it states that for the 3 carucates and six bovates there was land for nine ploughs, with the King having two ploughs in lordship. Since Skegby and Sutton are listed in quite a different way from Mansfield's other dependencies (which have separate entries) it is tempting to assume that these two ploughs of the King were for Sutton and Skegby.

Thre were a total of 16 manors in huccan hahl, disregarding those which were clearly split due to partible inheritance.

DOMESDAY AND PRE-DOMESDAY OWNERSHIP.We are fortunate that in most cases the Domesday record gives us the TRE owner and the 1086 owner of the manors. (Strictly speaking, all the land was owned by the king, and we have tenants-in-chief actually holding land from the king, and tenants holding from the tenants-in-chief.)

Unfortunately, as with many other factors, Domesday studies are always complicated by the fact that the record is not always complete. Although we do have a complete record indicating the identity of the tenants-in-chief, we sometimes lack the name of either the TRE or Domesday tenants.

The only land held directly by the King was Sutton and Skegby, administered as part of the King's Manor of Mansfield.

Next in importance is the land held by William Peverel, a favourite of William the Conqueror and the man he frequently charged with holding the strategically more important manors. In huccan hahl he held about half the total territory - 47 bovates out of the 96.

The next largest land holder was Ralph son of Hugh, followed by Ralph of Buron and the King's Thane, whom we can identify as Aelfric, who held the smaller of the two Kirkby manors both before and after the Conquest - one of the few to survive unscathed.

Of the manors held by Ralph Hugh, Leofric was the pre-Domesday tenant of two. Teversal and Wansley, and Leofnoth was the tenant of the other two, Kirkby and Annesley. Were these two Englishmen brothers? In all four cases it appears that Ralph put in his own man after the Conquest. Peverel appears nearly always to have done this, as did Ralph Buron at Hucknall (Torkard).

THE QUESTION OF NEWBOLD. The Philimore translation of Domesday is firm that Newbold in the middle of 50 consecutive Broxtow entries, is unlikely to be Newbold in Bingham, as DG and EONS. It is probably Newbound, by Teversal, in Broxtow, called Newbold until the 18th century. EPNS 136.

This must be correct as far as Broxtow is concerned, but I feel some doubts about it being identified with Newbound by Teversal.

Although a lot can happen in a thousand years I find it difficult to accept that the present Newbound, consisting of only a couple of small farms and a 'road through wet ground' (the meaning of Dawgate) can be the remnants of the largest and taxably richest manor in the northern vill of huccan hahl.

Newbold carries the meaning 'new building', and I cannot help wondering if this was associated with the undoubted and massive clearing of the Huthwaite hill spur from its tip to its origin near the present Stanton Hill.

If this suggestion has merit then we cannot ignore the possible significance of the site of the DMV near Stubbing Farm. The suggestion gains additional strength when considered in the light of later work done by Peters on the significance of the Huthwaite Hiil Spur. I understand that this is to be published in a lecture to the Sutton Heritage Society, so I will merely paraphrase it here.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HUTHWAITE.The knowledge of Iron Age defences around the Huthwaite hill spur has recently been added to by the discovery by Mrs Jane Peters of what are almost certainly the remains of additional defences on the north side of the spur.

Place-name, evidence of extensive re-clearing of the hill spur, from its western tip to its base near Stanton Hill, strongly suggests that the whole site was re-settled in the period of the local Anglo-Saxon settlement.

In view of the comparatively poor quality of the land in that area (indicated also by the low use of the plough when compared to the Central and South-east vill, as shown in Table 3). Peters suggestion that this would have been done for military purposes carries weight.

The element þveit (Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon þvit) of Huthwaite, being most often associated with man-made structures, also adds strength to this suggestion of re-building of defences on this hill spur.

Such a massive defensive feature would have been associated with an administrative centre, and it is suggested that this was the Stubbing Farm DMW. The name 'Newbold' would be the perfect name for that new site. The Domesday record shows Newbound to have fewer ploughs than Teversal, although it had twice the taxable value. This too adds strength to the evidence that the hill spur was largely non-agricultural.

Most recently we have Peters' suggestion - communicated to me in a transatlantic telephone call after I had completed this paper - that the name Whiteborough, common around the northern side of the hill spur, might derive from þwit and berg, meaning 'hill clearing' or 'fortification clearing'. Some scholars may doubt that þwit could mutate to 'white', but Ekwall considers it likely in the case of Inglewhite (Lancs) and Lilywhite (Durham).

My own view is that Peters' suggestion was inspirational, and may be appropriate to other names in 'white'. It makes sense to suggest that the Viking þveit mutates to 'thwaite' and the Anglo-Saxon þwit mutates to 'white'.

THE KING'S SKEGBY AND SUTTON.why just these two estates held by the King? Could it have been that, situated as they are across the base end of the hill spur, they were too important to be left in other hands? This would also explain why they were later transferred to Mansfield, for once the defensive nature of the hill spur was no longer necessary (ie after the absorption of Middle Anglia by Mercia) then it would have made bureaucratic sense to administer if from the nearest King's Manor, ie at Mansfield.

THE DOMESDAY MAP.If Ault Hucknall was indeed part of huccan hahl, and it now seems impossible to dispute this, then we are left with the certainty that this manor was included in the Nottinghamshire Domesday, and that therefore the Domesday map of this part of the county boundary should be re-drawn to include Ault Hucknall and the later Hardwick.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. Readers will be aware of my great debt to Roy Peters, whose work on pre-Domesday Nottinghamshire is of unparalleled extent and quality. His charming wife Jane is a historian with more common sense than the average academic, and kept the two of us on track. (I cannot avoid saying also that she got me to appreciate English tea, and taught me that since we in the USA cannot use electric kettles then we have a better chance than that average English home of making a proper cuppa'.)

To the Nottinghamshire County Library Service, particularly at Sutton, who gave much expert and unstinting help. Sutton is very fortunate in the service it gets from its librarians.

November 96 by Dr W.K. Grant Updated 18 Apr 04