Huthwaite War Memorial

Home War Efforts

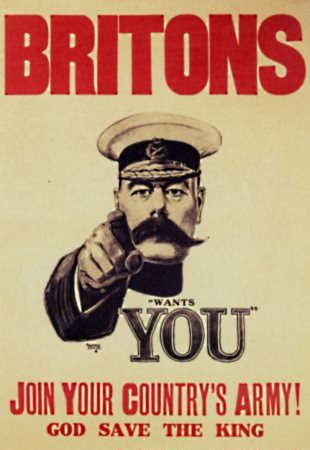

Many menfolk obviously followed the nations call for duty through two world wars. Lord Kitchener firstly rallied troops presenting this iconic poster.  Huthwaite did, nonetheless, also share other supportive war efforts.

Huthwaite did, nonetheless, also share other supportive war efforts.

The First World War now outstretches living memory. Traumatised veterans rarely spoke of the conflicts witnessed abroad. Those historically exposed events simply overshadowed any acknowledged hardships keeping homes eagerly awaiting their speedy return.

From initial outset, our government passed a Defence of the Realm Act

. That introduced cautious restrictions of little noticeable relevance here, except it introduced the presently accepted British summer time to give more daylight working hours. Despite best hopes for a swift end, warring continued draining national resources, especially after German u-boats disrupted regular imports. Workers from past generations mostly retold a shortage of bread, amid rising food costs. Otherwise, any resulting rationing of barely afforded luxuries caused little greater hardship, until realising the dramatic loss of so many lives. Veterans could only express luck, for not being among the considerable death toll, unwilling to retell horrors that commonly provoked nightmares.

Recovering from the impoverishing expense of war would not be easy, and may arguably have triggered a global economic recession. Government restricted coal output, so jobs at Huthwaite and neighbouring colliery areas were risking potential closure. Rising long term unemployment was an issue raised April 1932 in the House of Commons by Mr. C. Brown, M.P. for the Mansfield Division. That same year also reports Sutton and Huthwaite Urban Councillors assisting local unemployed recreational facilities. One councillor adds plea for disarming. Few envisaged traumatic necessity of entering into yet another Great War.

World War Two

No disrespect intended when its generally agreed that wartime rationing likely affected city dwellers rather more than smaller rural communities. Alongside the Derbyshire borderline, localities shared cheaper lifestyles supported off the land.  Wild game pestered farm meadows, readily sporting hare or rabbit as a favoured cheap meat. Gardening sustained very competitive, healthily productive pastimes, and a post WWI clearance of degraded housing found replacement council properties benefited a large allotment. Those hearing cry "Dig for Victory" just after outbreak of WWII, echoed similar announced slogans made by the Ministry of Agriculture. Prize winning Huthwaite flower and celery growers trusts they could cultivate more nutritional crops when needed. Furthermore to keeping pigeons, egg laying hens or ducks, besides diary farms, a back yard pig fed on wastes was never short of a butcher to share out everything except its squeal.

Wild game pestered farm meadows, readily sporting hare or rabbit as a favoured cheap meat. Gardening sustained very competitive, healthily productive pastimes, and a post WWI clearance of degraded housing found replacement council properties benefited a large allotment. Those hearing cry "Dig for Victory" just after outbreak of WWII, echoed similar announced slogans made by the Ministry of Agriculture. Prize winning Huthwaite flower and celery growers trusts they could cultivate more nutritional crops when needed. Furthermore to keeping pigeons, egg laying hens or ducks, besides diary farms, a back yard pig fed on wastes was never short of a butcher to share out everything except its squeal.

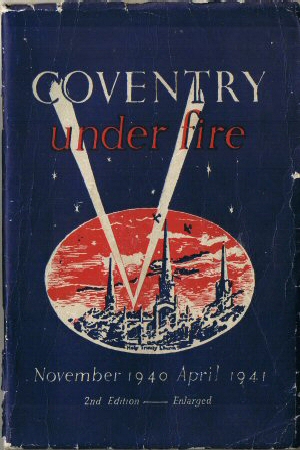

Progression into a second world war realised much more dramatic difference between industrial cities against small rural English settings. Germans rapidly smashed through Europe, capturing Paris and holding bases along the English Channel. Amid threat of Nazi troops managing to invade the British Isles, increasing range of mechanised warfare easily managing to blitz Sheffield, bringing frightening devastation nearer Nottingham, Derby and Chesterfield. Triangulated between those, most countryside districts fortunately presented no major target for enemy bombers, here realising relative safety for rehousing city evacuees. Nevertheless, this threatening reach over our coalfields had to be taken seriously. Following strict blackouts at least helped confuse aircraft navigation.

Air Raid Precautions

Precautionary measures included several air raid shelters, although elders recalled they were barely if ever used. Only known photo is in background to Barker Street VE Day celebrations. Similar bricked over stairwells apparently also stood off Clegg Hill Drive and Ashfield Road,  while personally remembering two still stood into late 1970's. One entrancing the Welfare Park off Sutton Road, plus cornering Huthwaite Market Place fronting "Clubby" doorway.

while personally remembering two still stood into late 1970's. One entrancing the Welfare Park off Sutton Road, plus cornering Huthwaite Market Place fronting "Clubby" doorway.

Many residents had the option of sharing bunkers beneath cellared homes when air raid sirens howled warning of flying dangers passing overhead. Mrs Nowell was one badged lookout warden given lofty CWS factory vantage point. Other wardens patrolled streets ensuring everyone strictly adhered to nightly blackouts.

Huthwaite heights viewed some glowing northerly skylines glimpsing Sheffield's fate. Two Huthwaite doctor brothers were training when devastation rained down on Coventry, recounted by their father. Huthwaite only ever got shook once by a few inexplicably dropped bombs. They harmlessly exploded near pit railways at Fulwood Cutting. Bigger scare came at New Street School when a child proudly presented classmates an unexploded incendiary bomb. Apparently, one of several innocently carried trophies brought from Coventry by evacuee children, as found stashed among old Common Road terraces where my great grandmother helped house some of those city victims.

Evacuee Children

Sutton railway stations welcomed arrival of well over a thousand evacuee children. As well as the Birmingham blitz, threat of 1940 Nazi invasion gave reason for evacuating one Essex school. A three year old Frances Clamp joined her elder sisters school mates safely removed from St Mary's C of E Primary, Southend on Sea. Frances remembers happily staying with Mr & Mrs 'B' in Common Road cottages before joined by mother and grandmother. Mrs Coupe accommodated her family in large rooms at The Orchards.

Drilling of Troops

Retaining first war addressed use for a Huthwaite Drill Hall, the New Hucknall Colliery Institute on Newcastle Street again became our village centre for billeting and basic training of raw recruits. One soldier from Birmingham is found sharing training experience in Huthwaite. Retelling his enrolment shows just how broadly The Sherwood Foresters filled their Notts. and Derbys. regiments. Additional billeting became needed to accommodate trainee soldiers. Armed troops also sharing rooms in homes among Ashfield Road. The old National School was much utilised, while commandeering more room at the Sutton Road Methodist Chapel.

The Home Guard

While trainee soldiers marched these streets and held square bashing upon Huthwaite Market Place, they were similarly joined by another uniformed force. From May 1940 the nation readily grouped Local Defence Volunteers to face threatening reality against invasion by German forces. Renamed a few months later by Churchill, the Home Guard largely consisted of men already holding a reserved occupation. All disciplined exercises held around the village were eagerly followed by children happily playing outdoors.

Royal Navy Medical Supplies

Seems strange to associate an area remotest from high seas with a British Royal Navy depot. Nonetheless, secretive Admiralty Fleet Orders dated 2nd April 1942, confirm Huthwaite was their main medical depot supplying home and abroad. Few residents were ever aware that a recently extended Huthwaite CWS factory offered a safe base for nationally receiving and internationally dispatching Naval Medical supplies. Bernard O'Connor was only a young child when his fathers work in London as a Navy Store man in Medical Supplies transferred them to Huthwaite circa 1941. They lodged with a family on North Street for a few years until Thomas O'Connor was again reposted. Postal efficiency of this Naval base, plus alternative manufacturing of combat clothing must now confirm this vast factory additionally served as an army store fully kitting out and arming all those Drill Hall troop trainees.

Bevin Boys

Reserved occupations certainly included skilled coal miners. Nevertheless, large groups readily enlisted. A tour of duty offered an heroic escape from undervalued, dirty and dangerous underground conditions. Joint war efforts found a heavily depleted workforce continuing to mine, manufacture, farm and market limited supplies. Home life had to be maintained while supporting our troops. Elsewhere, coal hungry industries turned into equipping armed land, sea and air forces which enticed young men away from such jobs. In desperation to replace lost miners, Ernest Bevin masterminded a random ballot scheme among recruits. Relocating some with great dismay into pit work, his Bevin Boys also arrived to man New Hucknall Colliery. A few ended up choosing to stay.

Prisoner of War Camp

Simple fact often retold was Huthwaite sited a WWII Prisoner of War Camp. Youngsters memories from passing the guarded compound below Common Road, or its escorted Italian workers are sketchy. It was after all frowned upon to fraternise with enemy groups. Without photos or documented evidence even from National Archives, it proved difficult just dating its existence. But with thanks extending to Mr. Fredrick Pote in Cornwall for shedding light upon an otherwise unidentified camp, based upon his 1946 soldering prison guard duties a little bit more of our history finally becomes revealed, including German and Ukrainian workers.

War Relief Funding

Huthwaite held numerous wartime fund raising events. They went beyond assisting church folk sending out comforting parcels to our troops abroad. Huthwaite contributed to the Sutton-in-Ashfield district raising well above the £5,000 covering cost of a new spitfire. Lord Beaverbrook offered his congratulations in November 1940, when Committee members aptly chose to name The Silver Snipe

17 Mar 12 by Gary Elliott Updated 09 Oct 20